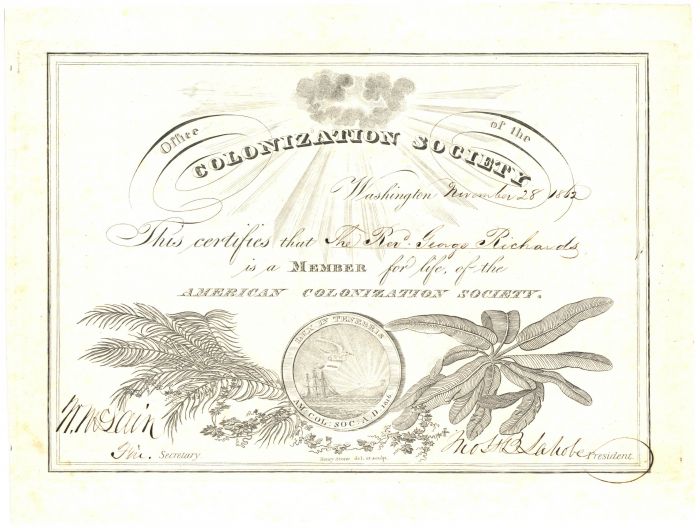

American Colonization Society Certificate dated 1862 - Stock Certificate

Inv# AM1537 Stock

American Colonization Society Certificate dated 1862 - By 1867, this Society sent back 13,000 Emigrants back to Africa.

The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, commonly known as the American Colonization Society (ACS), was founded in 1816 by Robert Finley, to encourage and support the voluntary migration of free African Americans to the continent of Africa.

There were several factors that led to the establishment of the American Colonization Society. The number of freed slaves and their descendants grew steadily since the American Revolutionary War, and slaveholders were concerned about the free Blacks' ability to aid their slaves to escape or to form a slave rebellion. It was also believed by many that because of white racism, the "amalgamation" (integration) of African Americans with mainstream American culture was out of the question. They needed to go somewhere else, where they could live free of white prejudices.

The African-American community was overwhelmingly opposed to the project; in many cases their families had lived in the United States for generations, and they said they were no more African than the Americans were British. Contrary to stated claims that emigration was voluntary, some Blacks were pressured to emigrate; in some cases slaves were manumitted (freed) on condition that they immediately emigrate. Blacks did not want to have the decision made for them.

"Colonization proved to be a giant failure, doing nothing to stem the forces that brought the nation to Civil War." Between 1821 and 1847 only a few thousand blacks, out of the millions of African Americans, emigrated to what would become Liberia. A large number of them died from tropical diseases. In addition, the transportation of the emigrants and providing them with tools and supplies was very expensive.

Starting in the 1830's the Society was met with great hostility from white abolitionists, led by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator, who proclaimed the Society a fraud. According to Garrison and his many followers, the Society was not a solution to the problem of American slavery; it actually was helping, and was intended to help, to preserve it.

Following the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the institution of slavery and those bound within it grew. During the early 19th century, the domestic slave trade resulted in the relocation of one million slaves to the Deep South, driven by demand for labor as cotton plantations were established following invention of the cotton gin at the very end of the eighteenth century. The enslaved Africans and African Americans had become well established and had children; the total number of slaves reached four million by the mid-19th century.

Due in part to manumission efforts sparked by revolutionary ideals, Protestant preachers, and the abolitionist movement, there was an expansion in the number of free blacks, many of them born free. Even in the North, where slavery was being abolished, they faced legislated limits on their rights.

Some slave owners decided to support emigration following an aborted slave rebellion headed by Gabriel Prosser in 1800, and a rapid increase in the number of free African Americans in the United States in the first two decades after the Revolutionary War, which they perceived as threatening. Although the ratio of whites to blacks overall was 4:1 between 1790 and 1800, in some Southern counties blacks were the majority. Slaveholders feared that free blacks destabilized their slave society and created a political threat. From 1790 to 1800, the number of free blacks increased from 59,467 to 108,398, and by 1810 there were 186,446 free blacks.

In 1786, a British organization, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, launched its efforts to establish the Sierra Leone Province of Freedom, their colony in West Africa, for London's "black poor". This enterprise gained the support of the British government, which also offered relocation to Black Loyalists who had been resettled in Nova Scotia, where they were subject to harsh weather and discrimination from white colonists. Britain further deported Jamaica maroons to this colony, as well as captives which its navy took from illegal slave ships after the Atlantic slave trade was banned in 1807.

Paul Cuffe or Cuffee (1759–1817) was a successful Quaker ship owner and activist in Boston. His parents were of Ashanti (African) and Wampanoag (Native American) heritage. He advocated settling freed American slaves in Africa and gained support from the British government, free Black leaders in the United States, and members of Congress to take emigrants to the British colony of Sierra Leone. In 1815, he financed a trip himself. The following year, Cuffe took 38 American blacks to Freetown, Sierra Leone. He died in 1817 before undertaking other voyages. Cuffe laid the groundwork for the American Colonization Society.

The ACS had its origins in 1816, when Charles Fenton Mercer, a Federalist member of the Virginia General Assembly, discovered accounts of earlier legislative debates on black colonization in the wake of Gabriel Prosser's rebellion. Mercer pushed the state to support the idea. One of his political contacts in Washington City, John Caldwell, in turn contacted the Reverend Robert Finley, his brother-in-law and a Presbyterian minister, who endorsed the plan.

On December 21, 1816, the society was officially established at the Davis Hotel in Washington, D.C.. Among the Society's supporters were Charles Fenton Mercer (from Virginia), Henry Clay (Kentucky), John Randolph (Virginia), Richard Bland Lee (Virginia), and Bushrod Washington (Virginia). Slaveholders in the Virginia Piedmont region in the 1820s and 1830s comprised many of its most prominent members; slave-owning United States presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison were among its supporters. Madison served as the Society's president in the early 1830s.

At the inaugural meeting of the Society, Reverend Finley suggested that a colony be established in Africa to take free people of color, most of whom had been born free, away from the United States. Finley meant to colonize "(with their consent) the free people of color residing in our country, in Africa, or such other place as Congress may deem most expedient". The organization established branches throughout the United States, mostly in Southern states. It was instrumental in establishing the colony of Liberia.

The ACS was founded by groups otherwise opposed to each other on the issue of slavery. Slaveholders, such as those in the Maryland branch and elsewhere, believed that so called repatriation was a way to remove free blacks from slave societies and avoid slave rebellions. Free blacks, many of whom had been in the United States for generations, also encouraged and assisted slaves to escape, and depressing their value. ("Every attempt by the South to aid the Colonization Society, to send free colored people to Africa, enhances the value of the slave left on the soil.") The Society appeared to hold contradictory ideas: free blacks should be removed because they could not benefit America; on the other hand, free blacks would prosper and thrive under their own leadership in another land.

On the other hand, a coalition made up mostly of evangelicals, Quakers, philanthropists, and abolitionists supported abolition of slavery. They wanted slaves to be free and believed blacks would face better chances for freedom in Africa than in the United States, since they were not welcome in the South or North. The two opposed groups found common ground in support of repatriation.

The presidents of the ACS tended to be Southerners. The first president was Bushrod Washington, the nephew of U.S. President George Washington and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. From 1836 to 1849 the statesman Henry Clay of Kentucky, a planter and slaveholder, was ACS president. John H. B. Latrobe served as president of the ACS from 1853 until his death in 1891.

The colonization project, which had multiple American Colonization Society chapters in every state, had three goals. One was to provide a place for former slaves, freedmen, and their descendants to live, where they would be free and not subject to racism. Another goal was to ensure that the colony had what it needed to succeed, such as fertile soil to grow crops. A third goal was to suppress attempts to engage in the Atlantic slave trade, such as by monitoring ship traffic on the coast. Presbyterian clergyman Lyman Beecher proposed another goal: the Christianization of Africa.

The Society raised money by selling memberships. The Society's members pressured Congress and the President for support. In 1819, they received $100,000 from Congress, and on February 6, 1820, the first ship, the Elizabeth, sailed from New York for West Africa with three white ACS agents and 88 African-American emigrants aboard. The approaches for selecting people and funding travel to Africa varied by state.

Originally, colonization "had been pushed with diligence and paraded as the cure for the evils of slavery, and its benevolence was assumed on all hands. Everybody of consequence belonged to it." The following summary is from April of 1834:

The plan of colonizing free blacks, has been justly considered one of the noblest devices of Christian benevolence and enlightened patriotism, grand in its object, and most happily adapted to enlist the combined influence, and harmonious cooperation, of different classes of society. It reconciles, and brings together some discordant interests, which could not in any other plan be brought to meet in harmony. The Christian and the statesman here act together, and persons having entirely different views from each other in reference to some collateral points connected with the great subject, are moved towards the same point by a diversity of motives. It is a splendid conception, around which are gathered the hopes of the nation, the wishes of the patriot, the prayers of the Christian, and we trust, the approbation of Heaven.

The colonization movement "originated abolitionism", by arousing the free blacks and other opponents of slavery.

From the beginning, "the majority of black Americans regarded the Society [with] enormous disdain." Black activist James Forten immediately rejected the ACS, writing in 1817 that "we have no wish to separate from our present homes for any purpose whatever". Frederick Douglass, commenting on colonization, "Shame upon the guilty wretches that dare propose, and all that countenance such a proposition. We live here — have lived here — have a right to live here, and mean to live here." Martin Delany, who believed that Black Americans deserved "a new country, a new beginning", called Liberia a "miserable mockery" of an independent republic, a "racist scheme of the ACS to rid the United States of free blacks". He proposed instead Central and South America as "the ultimate destination and future home of the colored race on this continent".

African Americans viewed colonization as a means of defrauding them of the rights of citizenship and a way of tightening the grip of slavery. ...The tragedy was that African Americans began to view their ancestral home with disdain. They dropped the use of "African" in names of their organizations...and used instead [of African American] "The Colored American."

While claiming to aid African Americans, in some cases, to stimulate emigration, it made conditions for them worse. For example, "the Society assumed the task of resuscitating the Ohio Black Codes of 1804 and 1807. ...Between 1,000 and 1,200 free blacks were forced from Cincinnati." A meeting was held in Cincinnati on January 17, 1832 to discuss colonization, which resulted in a series of resolutions. First, they had a right to freedom and equality. They felt honor-bound to protect the country, the "land of their birth", and the constitution. They were not familiar with Africa, and should have the right to make their own decisions about where they lived. They recommended that if black people wish to leave the United States, they consider Canada or Mexico, where they would have civil rights and a climate that is similar to what they are accustomed. The United States was large enough to accommodate a colony, and would be much cheaper to implement. They question the motives of ACS members who cite Christianity as a reason for removing blacks from America. Since there were no attempts to improve the conditions of black people who lived in the United States, it is unlikely that white people would watch out for their interests thousands of miles away.

William Garrison began publication of his abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831, followed in 1832 by his Thoughts on African Colonization. President Lincoln credited Garrison with "first putting emancipation on the country’s political agenda". Garrison, himself, joined it in good faith." All the important white future abolitionists supported it: besides Garrison, Gerrit Smith, the Tappans, and many others, as can be seen in the pages of the Society's African Repository.

Garrison objected to the colonization scheme because rather than eliminating slavery, the key goal was to remove free black people from America, thereby avoiding slave rebellions. Besides not improving the lot of enslaved Africans, the colonization had made enemies of native people of Africa. He did not approve with the marketing of alcohol and guns in Liberia. He questioned sending African-Americans to an unhealthy climate, which would also become populated with missionaries and agents, resulting in deaths. Colonization is expensive. In addition, "it hinders the manumission of slaves by throwing their emancipation upon its own scheme, which in fifteen years has occasioned the manumission of less than four hundred slaves, while before its existence and operations during a less time thousands were set free."

The philanthropist Gerrit Smith had been, as put by Society Vice-President Henry Clay, "among the most munificent patrons of this Society".

This support changed to furious and bitter rejection when they realized, in the early 1830's, that the society was, in Gerrit Smith's words, "quite as much an Anti-Abolition, as Colonization Society". "This Colonization Society had, by an invisible process, half conscious, half unconscious, been transformed into a serviceable organ and member of the Slave Power." It was "an extreme case of sham reform". In November of 1835, he sent the Society a letter with a check, to conclude his existing commitments, and said there would not be any more from him, because:

The Society is now, and has been for some time, far more interested in the question of slavery, than in the work of Colonization—in the demolition of the Anti-Slavery Society, than in the building up of its Colony. I need not go beyond the matter and spirit of the last few numbers of its periodical for the justification of this remark. Were a stranger to form his opinion by these numbers, it would be, that the Society issuing them was quite as much an Anti-Abolition, as Colonization Society. ...It has come to this, however, that a member of the Colonization Society cannot advocate the deliverance of his enslaved fellow men, without subjecting himself to such charges of inconsistency, as the public prints abundantly cast on me, for being at the same time a member of that Society and an Abolitionist. ...Since the late alarming attacks, in the persons of its members, on the right of discussion, (and astonishing as it is, some of the suggestions for invading this right are impliedly countenanced in the African Repository,) I have looked to it, as being also the rallying point of the friends of this right. To that Society yours is hostile.

In 1825 and 1826, Jehudi Ashmun, an early leader of the ACS, took steps to lease, annex, or buy tribal lands in Africa along the coast and along major rivers leading inland in Africa to establish an American colony. In 1821, Lt. Robert Stockton, Ashmun's predecessor, had pointed a pistol to the head of King Peter, which allowed Stockton to persuade King Peter to sell Cape Montserrado (or Mesurado) and to establish Monrovia. Stockton's actions inspired Ashmun to use aggressive tactics in his negotiations with King Peter and in May 1825, King Peter and other native kings agreed to a treaty with Ashmun. The treaty negotiated land to Ashmun and in return, the natives received three barrels of rum, five casks of powder, five umbrellas, ten pairs of shoes, ten iron posts, and 500 bars of tobacco, as well as other items.

The ship pulled in first at Freetown, Sierra Leone, from where it sailed south to what is now the northern coast of Liberia. The emigrants started to establish a settlement. All three whites and 22 of the emigrants died within three weeks from yellow fever. The remainder returned to Sierra Leone and waited for another ship. The Nautilus sailed twice in 1821 and established a settlement at Mesurado Bay on an island they named Perseverance. It was difficult for the early settlers, made of mostly free-born blacks who had been denied the full rights of United States citizenship. In Liberia, the native Africans resisted the expansion of the colonists, resulting in many armed conflicts between them. Nevertheless, in the next decade 2,638 African Americans migrated to the area. Also, the colony entered an agreement with the U.S. Government to accept freed slaves who were taken from illegal slave ships.

According to J. N. Danforth, "General Agent" of the Society, as of 1832 "The legislature[s] of fourteen States, among which are New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Ohio, and Indiana, and nearly all the ecclesiastical bodies in the United States[,] have recommended the Society to the patronage of the American people."

From the establishment of the colony, the American Colonization Society had employed white agents to govern the colony. In 1842, Joseph Jenkins Roberts became the first non-white governor of Liberia. In 1847, the legislature of Liberia declared itself an independent state, with Roberts as its first President.

The society in Liberia developed into three segments:

- Settlers from the United States, or Afro-Americans,

- Freed slaves from (illegal) slave ships and the West Indies, and

- Indigenous native peoples like the Mande.

Each of these groups would have a profound effect on the history of Liberia.

Tropical diseases were a major problem for the settlers, and the new immigrants to Liberia suffered the highest mortality rates since accurate record-keeping began. Of the 4,571 emigrants who arrived in Liberia between 1820 to 1843, only 1,819 were alive in 1843. The ACS knew of the high death rate, but continued to send more people to the colony. Professor Shick writes:

[T]he organization continued to send people to Liberia while very much aware of the chances for survival. The organizers of the A.C.S. considered themselves to be humanitarians performing the work of God. This attitude prevented them from accepting certain realities of their crusade. Any problems, including those of disease and deaths, were viewed as the trials and tribulations that God provides as a means of testing the fortitude of man. After every report of disaster in Liberia the managers simply renewed their efforts. Once the organization was formed and the auxiliaries established, a new force developed which also prevented the Society from admitting the seriousness of the mortality problem. The desire to perpetuate the existence of the corporate body became a factor. To have admitted that the mortality rate made the price of emigration far too high to be continued would have meant the end of the organization. The managers were seemingly unprepared to advise the termination of their project and by extension, their own jobs.

Beginning in 1825, the Society published the African Repository and Colonial Journal. Ralph Randolph Gurley (1797–1872), who headed the Society until 1844, edited the journal, which in 1850 simplified its title to African Repository. The journal promoted both colonization and Liberia. Included were articles about Africa, lists of donors, letters of praise, information about emigrants, and official dispatches that espoused the prosperity and continued growth of the colony. After 1919, the society essentially ended, but it did not formally dissolve until 1964, when it transferred its papers to the Library of Congress.

Since the 1840s, Lincoln, an admirer of Clay, had been an advocate of the ACS program of colonizing blacks in Liberia. Early in his presidency, Abraham Lincoln tried repeatedly to arrange resettlement of the kind the ACS supported, but each arrangement failed.

The ACS continued to operate during the American Civil War, and colonized 168 blacks while it was being waged. It sent 2,492 blacks to Liberia in the following five years. The federal government provided a small amount support for these operations through the Freedmen's Bureau.

Some scholars believe that Lincoln abandoned the idea by 1863, following the use of black troops. Biographer Stephen B. Oates has observed that Lincoln thought it immoral to ask black soldiers to fight for the U.S. and then to remove them to Africa after their military service. Others, such as the historian Michael Lind, believe that as late as 1864, Lincoln continued to hold out hope for colonization, noting that he allegedly asked Attorney General Edward Bates if the Reverend James Mitchell could stay on as "your assistant or aid in the matter of executing the several acts of Congress relating to the emigration or colonizing of the freed Blacks". Mitchell, a former state director of the ACS in Indiana, had been appointed by Lincoln in 1862 to oversee the government's colonization programs.

By late into his first term as president, Lincoln had publicly abandoned the idea of colonization after speaking about it with Frederick Douglass, who objected harshly to it. On April 11, 1865, with the war drawing to a close, Lincoln gave a public speech at the White House supporting suffrage for blacks, a speech that led actor John Wilkes Booth, who was vigorously opposed to emancipation and black suffrage, to assassinate him.

Colonizing proved expensive; under the leadership of Henry Clay the ACS spent many years unsuccessfully trying to persuade the U.S. Congress to fund emigration. The ACS did have some success, in the 1850s, with state legislatures, such as those of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. In 1850, the state of Virginia set aside $30,000 annually for five years to aid and support emigration. The Society, in its Thirty-fourth Annual Report, acclaimed the news as "a great Moral demonstration of the propriety and necessity of state action!" During the 1850s, the Society also received several thousand dollars from the New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Missouri, and Maryland legislatures. Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Mississippi set up their own state societies and colonies on the coast next to Liberia. However, the funds that ACS took in were inadequate to meet the Society's stated goals. "For the fourteen years preceding 1834, the receipts of that society, needing millions for its proposed operations, had averaged only about twenty-one thousand dollars a year. It had never obtained the confidence of the American people".

Three of the reasons the movement never became very successful were lack of interest by free blacks, opposition by some abolitionists, and the scale and costs of moving many people (there were 4 million freedmen in the South after the Civil War). There were millions of black slaves in the United States, but colonization only transported a few thousand free blacks.

In 1913, and again at its formal dissolution in 1964, the Society donated its records to the U.S. Library of Congress. The donated materials contain a wealth of information about the founding of the society, its role in establishing Liberia, efforts to manage and defend the colony, fundraising, recruitment of settlers, conditions for black citizens of the American South, and the way in which black settlers built and led the new nation.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, the ACS sent a cablegram to President Daniel Howard of Liberia, warning him that any involvement in the war could lead to Liberia's territorial integrity being violated regardless of which side might come out on top.

In Liberia, the Society maintained offices at the junction of Ashmun and Buchanan Streets at the heart of Monrovia's commercial district, next to the True Whig Party headquarters in the Edward J. Roye Building. Its offices at the site closed in 1956 when the government demolished all the buildings at the intersection for the purpose of constructing new public buildings there. Nevertheless, the land officially remained the property of the Society into the 1980s, amassing large amounts of back taxes because the Ministry of Finance could not find an address to which to send property tax bills.

Beginning in the 1950s, racism was an increasingly important issue and by the late 1960s and 1970s it had been forced to the forefront of public consciousness by the civil rights movement. The prevalence of racism invited a revaluation of the Society's motives, prompting historians to examine the ACS in terms of racism more than its stance on slavery. By the 1980s and 1990s, historians were going even further in reimagining the ACS. Not only were they focusing on the racist rhetoric of the Society's members and publications, but some also depicted the Society as proslavery organization. Recently, however, the winds have shifted again with scholars retreating from an analysis of the ACS as proslavery, and with some cautiously characterizing it as an antislavery organization again.

Signed by John Hazelhurst Boneval Latrobe (1803–1891) was an American lawyer and inventor. He invented the Latrobe Stove, also known as the "Baltimore Heater", a coal fired parlor heater made of cast iron and that fit into fireplaces as an insert. He patented his design in 1846. The squat stoves were very popular by the 1870s and were much smaller than Benjamin Franklin's Franklin stove.

He was the son of noted engineer and architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. John Latrobe secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, where he studied engineering (1818-1821). However, he ultimately decided to become a lawyer, and returned to Baltimore after his father's death to read law under the director of Robert Goodloe Harper. He married twice. His first wife, Margaret Caile Steuart (1795-1831), bore one son, Henry Boneval Latrobe (1830-1877) before her death. He remarried in Natchez, Mississippi in 1832 to Charlotte Virginia Claiborne, (1815-1903) who would survive him and also bear seven children.

A lawyer after admission to the Maryland bar, this Latrobe initially practiced with his younger brother, Benjamin Henry Latrobe II, until the younger Latrobe decided to concentrate on civil engineering, as had their father. John H.B. Latrobe became a lawyer for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, initially arranging for land acquisitions (and publishing a work about conveyancing in 1826). He later incorporated its telegraph service, and become its chief counsel for decades. He would negotiate with the Choctaw, Chickasaw and other tribes, as well travel to Russia before the American Civil War to negotiate financing.

As a patent lawyer, Latrobe was reluctant to take credit for his stoves, believing being known as an inventor of stoves would damage his legal reputation. Over 300,000 of the stoves were in use by 1878, although in recent decades, antique stoves such as the Latrobe are collected but rarely used for their original purpose, being more often used as decoration or as planters. In 1871 he delivered a lecture on the history of the steamboat which explained the contribution of Nicholas Roosevelt, who had married his elder half-sister Lydia Sellon Latrobe.

Latrobe was a long-time supporter of the effort to establish a home in Africa for emancipated slaves. Succeeding Senator Henry Clay, Latrobe served as president of the American Colonization Society from 1853 until his death in 1891. He also helped found the Maryland Historical Society, of which he was president, and the American Bar Association. Latrobe gave a speech about history of the Mason–Dixon line to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1854 which was widely reprinted, and also helped found Druid Hill Park, serving on its Board of Directors from 1860 until his death. Latrobe also achieved some distinction as a poet and painter, and was one of the 3-judge panels which awarded Edgar Allan Poe a prize for his "Manuscript in a bottle", which was published in Baltimore's Sunday Visitor paper and helped launch the writer's career.

Latrobe died in 1891 and was buried with other family members in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore. Latrobe donated his family's papers, including an autobiography he wrote, to Maryland's State Archives, which continue to maintain them. A biography of him published in 1917 remains accessible through the Internet archive. His Baltimore home continues to stand across from Baltimore's Catholic Basilica, which his father had designed (and he may have helped design the facing portico).

His son Ferdinand C. Latrobe (1833–1911) became a lawyer and author like his father served in the Maryland legislature and was elected Baltimore's mayor seven times.

A stock certificate is issued by businesses, usually companies. A stock is part of the permanent finance of a business. Normally, they are never repaid, and the investor can recover his/her money only by selling to another investor. Most stocks, or also called shares, earn dividends, at the business's discretion, depending on how well it has traded. A stockholder or shareholder is a part-owner of the business that issued the stock certificates.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries