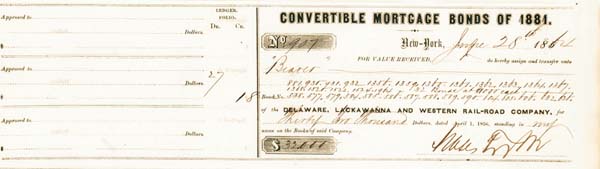

Moses Taylor signed Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Transfer Receipt

Inv# AG1209 Bond

Moses Taylor (January 11, 1806 – May 23, 1882) was a 19th-century New York merchant and banker and one of the wealthiest men of that century. At his death, his estate was reported to be worth $70 million, or about $1.9 billion in today's dollars. He controlled the National City Bank of New York (later to become Citibank), the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western railroad, and the Moses Taylor & Co. import business, and he held numerous other investments in railroads and industry.

Taylor was born on January 11, 1806 to Jacob B. Taylor and Martha (née Brant) Taylor. His father was a close associate of John Jacob Astor and acted as his agent by purchasing New York real estate while concealing Astor's interest. Astor's relationship with the Taylor family provided Moses with an early advantage.

At age 15, Moses Taylor began working at J. D. Brown shippers. He soon moved to a clerk's position in the firm of Gardiner Greene Howland and Samuel Howland's firm G. G. & S. Howland Company of New York, a shipping and import firm that traded with South America.

By 1832, at age 26, Moses had sufficient wealth to marry, leave the Howland company, and start his own business as a sugar broker. As such he dealt with slave-owning Cuban sugar growers, found buyers for their product, exchanged currency, and advised and assisted them with their investments. He nurtured relationships with those slave-owners, who relied on him for loans and investments to support their plantations. Taylor never visited Cuba, but his friendship with Henry Augustus Coit, a prominent trader who was fluent in Spanish, enabled him to trade with the Cuban growers. Taylor soon discovered that loans and investments provided returns that were as good as, or better than, those from the sugar business, although the sugar trade remained a core source of income. By the 1840s his income was largely from interest and investments. By 1847, Moses Taylor was listed as one of New York City's 25 millionaires.

When the Panic of 1837 allowed Astor to take over what was then City Bank of New York (today known as Citibank), he named Moses Taylor as director. Moses himself had doubled his fortune during the panic, and brought his growing financial connections to the bank. He acquired equity in the bank and in 1855 became its president, operating it largely in support of his and his associates' businesses and investments.

In the 1850s Moses invested in iron and coal, and began purchasing interest in the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western railroad. When the Panic of 1857 brought the railroad to the brink of bankruptcy, Moses obtained control by purchasing its outstanding shares for $5 a share. Within seven years the shares became worth $240, and the D. L. & W was one of the premier railroads of the country. By 1865 Moses held 20,000 shares worth almost $50 million.

Moses held an interest in the New York, Newfoundland, and London Telegraph Company that Cyrus West Field had founded in 1854. Although its attempts to lay a cable across the Atlantic were initially unsuccessful, it eventually succeeded and in 1866 became the first transatlantic telegraph company.

Taylor also had controlling interest in the largest two of the seven gas companies in Manhattan that were merged (after his death) to form the Consolidated Gas Company in 1884, eventually becoming Consolidated Edison. Taylor's Manhattan Gas Company and New York Gas Light Company were 45% of the merged Consolidated Gas, and his descendants remained some the largest individual shareholders of Consolidated Edison.

After the Civil War, during which he assisted the Union with financing the war debt, he continued to invest in iron, railroads, and real estate. His real estate holdings in New York brought him into close association with Boss Tweed of New York's Tammany Hall. Moses sat in 1871 on a committee made up of New York's most influential and successful businessmen and signed his name to a report that commended Tweed's controller for his honesty and integrity. This report was considered a notorious whitewash.

Taylor was married to Catharine Anne Wilson (1810–1892). Together, they were the parents of:

- Albertina Shelton Taylor (1833–1900), who married Percy Rivington Pyne (1820–1895) in 1855. Pyne, an assistant to Moses, became president of City Bank upon Moses' death.

- Mary Taylor (1837–1907), who married George Lewis (1833–1888)

- George Campbell Taylor (1837–1907)

- Katherine Wilson Taylor (1839–1925), who married Robert Winthrop

- Henry Augustus Coit Taylor (1841–1921), who married Charlotte Talbot Fearing (1845–1899) in 1868. After her death, he married Josephine Whitney Johnson (1849–1927) in 1903. Taylor left an estate worth $50 million upon his death in 1921, just a few months before the death of his nephew Moses Taylor Pyne.

Moses died in 1882 and although he owned a vault at the New York City Marble Cemetery that already contained members of his family, he was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York City. Moses left his fortune to his wife and children. Many of the Taylor family descendants were prominent in New York and Newport society and several prominent families owe a substantial portion of their fortunes to the Taylor inheritances.

Through his daughter Albertina, the Pynes family became a dynasty of bankers that survives to this day. Percy's son Moses Taylor Pyne was a benefactor of Princeton University who supported its development from a college into a university and left an estate worth $100 million at his death in 1921.

Through his daughter Katherine, he was a grandfather of Hamilton Fish Kean (1862–1941), ancestor of the political Kean family which includes the former governor of New Jersey Thomas Kean.

Not noted for philanthropy during his life, at its end in 1882 Moses Taylor donated $250,000 to build a hospital in Scranton, Pennsylvania to benefit his iron and coal workers, and workers of the D. L. & W railroad. The Moses Taylor hospital continues in operation today.The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (also known as the DL&W or Lackawanna Railroad) was a U.S. Class 1 railroad that connected Buffalo, New York, and Hoboken, New Jersey (and by ferry with New York City), a distance of about 400 miles (640 km). Incorporated in 1853, the DL&W was profitable during the first two decades of the twentieth century, but its margins were gradually hurt by declining traffic in coal and competition from trucks. In 1960, the DL&W merged with rival Erie Railroad to form the Erie Lackawanna Railroad.

The "Leggett's Gap Railroad" was incorporated on April 7, 1832, but stayed dormant for many years. It was chartered on March 14, 1849, and organized January 2, 1850. On April 14, 1851, its name was changed to the "Lackawanna and Western Railroad". The line, running north from Scranton, Pennsylvania, to Great Bend, just south of the New York state line, opened on December 20, 1851. From Great Bend the L&W obtained trackage rights north and west over the New York and Erie Rail Road to Owego, New York, where it leased the Cayuga and Susquehanna Railroad to Ithaca on Cayuga Lake (on April 21, 1855). The C&S was a re-organized and partially re-built Ithaca and Owego Railroad, which had opened on April 1, 1834, and was the oldest part of the DL&W system. The whole system was built to 6 ft (1,829 mm) broad gauge, the same as the New York and Erie, although the original I&O was built to standard gauge and converted to wide gauge when re-built as the C&S.

The "Delaware and Cobb's Gap Railroad" was chartered December 4, 1850, to build a line from Scranton east to the Delaware River. Before it opened, the Delaware and Cobb's Gap and Lackawanna and Western were consolidated by the Lackawanna Steel Company into one company, the "Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad", on March 11, 1853. On the New Jersey side of the Delaware River, the Warren Railroad was chartered February 12, 1851, to continue from the bridge over the river southeast to Hampton on the Central Railroad of New Jersey. That section got its name from Warren County, the county through which it would primarily run.

The rest of the line, now known as the Southern Division, opened on May 27, 1856, including the New Jersey section (the Warren Railroad). A third rail was added to the standard gauge Central Railroad of New Jersey east of Hampton to allow the DL&W to run east to Elizabeth via trackage rights (the CNJ was extended in 1864 to Jersey City).

On December 10, 1868, the DL&W bought the Morris and Essex Railroad. This line ran east–west across northern New Jersey, crossing the Warren Railroad at Washington and providing access to Jersey City without depending on the CNJ. The M&E tunnel under Bergen Hill opened in 1876, also relieving it of its use of the New York, Lake Erie and Western Railway in Jersey City. Along with the M&E lease came several branch lines in New Jersey, including the Boonton Line (opened in 1870), which bypassed Newark for through freight.

The DL&W bought the Syracuse, Binghamton and New York Railroad in 1869 and leased the Oswego and Syracuse Railroad on February 13, 1869. This gave it a branch from Binghamton north and northwest via Syracuse to Oswego, a port on Lake Ontario. The "Greene Railroad" was organized in 1869, opened in 1870, and was immediately leased to the DL&W, providing a short branch off the Oswego line from Chenango Forks to Greene. Also in 1870 the DL&W leased the Utica, Chenango and Susquehanna Valley Railway, continuing this branch north to Utica, with a branch from Richfield Junction to Richfield Springs (fully opened in 1872).

The "Valley Railroad" was organized March 3, 1869, to connect the end of the original line at Great Bend, Pennsylvania, to Binghamton, New York, avoiding reliance on the Erie. The new line opened October 1, 1871. By 1873, the DL&W controlled the Lackawanna and Bloomsburg Railroad, a branch from Scranton southwest to Northumberland (with trackage rights over the Pennsylvania Railroad's Northern Central Railway to Sunbury). On March 15, 1876, the whole system was re-gauged to standard gauge in one day. The "New York, Lackawanna and Western Railroad" was chartered August 26, 1880, and opened September 17, 1882, to continue the DL&W from Binghamton west and northwest to Buffalo. The main line ran to the International Bridge to Ontario, and a branch served downtown Buffalo. A spur from Wayland served Hornellsville (Hornell). On December 1, 1903, the DL&W began operating the Erie and Central New York Railroad, a branch of the Oswego line from Cortland Junction east to Cincinnatus. That same year, they also began to control the Bangor and Portland Railway. By 1909, the DL&W controlled the Bangor and Portland Railway. This line branched from the main line at Portland, Pennsylvania southwest to Nazareth, with a branch to Martins Creek.

The DL&W built a Beaux-Arts terminal in Hoboken in 1907, and another Beaux-Arts passenger station (now a Radisson hotel) in Scranton the following year. A new terminal was constructed on the waterfront in Buffalo in 1917.

The "Lackawanna Railroad of New Jersey", chartered on February 7, 1908, to build the Lackawanna Cut-Off (a.k.a. New Jersey Cutoff or Hopatcong-Slateford Cutoff), opened on December 24, 1911. This provided a low-grade cutoff in northwestern New Jersey. The cutoff included the Delaware River Viaduct and the Paulinskill Viaduct, as well as three concrete towers at Port Morris and Greendell in New Jersey and Slateford Junction in Pennsylvania. From 1912 to 1915, the Summit-Hallstead Cutoff (a.k.a. Pennsylvania Cutoff or Nicholson Cutoff) was built to revamp a winding and hilly system between Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania, and Hallstead, Pennsylvania. This rerouting provided another quicker low-grade line between Scranton and Binghamton. The Summit Cut-Off included the massive Tunkhannock Viaduct and Martins Creek Viaduct. The Lackawanna's cutoffs had no at-grade crossings with roads or highways, allowing high-speed service.

The DL&W ran trains from its Hoboken Terminal, its gateway to the New York City market, to its Scranton, Syracuse, Oswego, Buffalo stations and to Utica Union Station. Noteworthy among these were:

- Nos. 2 Pocono Express / 5 Twilight (Hoboken-Buffalo, with New York Central connections to Chicago)

- Nos. 3 / 6 Phoebe Snow, nee Lackawanna Limited (Hoboken-Buffalo)

- Nos. 7 Westerner / 8 New Yorker (Hoboken-Buffalo, with Nickel Plate connections to Chicago)

- Nos. 10 New York Mail / 15 Owl (Hoboken-Buffalo)

- Nos. 1301 / 1306 Interstate Express (Philadelphia-Syracuse)

- Nos. 1702 Keystone Express / 1705 Pittsburgh Express (Scranton-Pittsburgh)

Additionally, the DL&W ran commuter operations from northern New Jersey suburbs to Hoboken on the Boonton, Gladstone, Montclair and Morristown Lines.

The most profitable commodity shipped by the railroad was anthracite coal. In 1890 and during 1920–1940, the DL&W shipped upwards of 14% of the state of Pennsylvania's anthracite production. Other profitable freight included dairy products, cattle, lumber, cement, steel, and grain. The Pocono Mountains region was one of the most popular vacation destinations in the country—especially among New Yorkers—and several large hotels sat along the line in Northeastern Pennsylvania, generating a large passenger traffic for the Lackawanna. All of this helped justify the railroad's expansion of its double-track mainline to three and in a few places four tracks.

Changes in the region's economy undercut the railroad, however. The post-World War II boom enjoyed by many U.S. cities bypassed Scranton, Wilkes-Barre and the rest of Lackawanna and Luzerne counties. Oil and natural gas quickly became the preferred energy sources. Silk and other textile industries shrank as jobs moved to the southern U.S. or overseas. The advent of refrigeration squeezed the business from ice ponds on top of the Poconos. Even the dairy industry changed. The Lackawanna had long enjoyed revenues from milk shipments; many stations had a creamery next to the tracks.

Perhaps the most catastrophic blows to the Lackawanna, however, were dealt by Mother Nature. In August 1955, flooding from Hurricane Diane devastated the Pocono Mountains region, killing 80 people. The floods cut the Lackawanna Railroad in 88 places, destroying 60 miles (97 km) of track, stranding several trains (with a number of passengers aboard), and shutting down the railroad for nearly a month (with temporary speed restrictions prevailing on the damaged sections of railroad for months), causing a total of $8.1 million in damages (equal to $77,307,205 today) and lost revenue. One section, the Old River line (former Warren Railroad), was damaged beyond repair and had to be abandoned altogether. Until the mainline in Pennsylvania reopened, all trains were cancelled or rerouted over other railroads. The Lackawanna would never fully recover.

In January, 1959, the final nail was driven in the Lackawanna's coffin by the Knox Mine Disaster, which flooded the mines along the Susquehanna River and all but obliterated what was left of the region's anthracite industry.

The Lackawanna Railroad's financial problems were not unique. Rail traffic in the U.S. in general declined after World War II as trucks and automobiles took freight and passenger traffic. Declining freight traffic put the nearby New York, Ontario and Western Railroad and Lehigh & New England Railroad out of business in 1957 and 1961, respectively. Over the next three decades, nearly every major railroad in the Northeastern US would go bankrupt.

In the wake of Hurricane Diane in 1955, all signs pointed to continued financial decline and eventual bankruptcy for the DL&W. Among other factors, property taxes in New Jersey were a tremendous financial drain on the Lackawanna and other railroads that ran through the state, a situation that would not be remedied for another two decades.

To save his company, Lackawanna president Perry Shoemaker sought a merger with the Nickel Plate Road, a deal that would have created a railroad stretching more than 1,100 miles (1,800 km) from St. Louis, Missouri, to New York City and would have allowed the Lackawanna to retain the 200 miles (320 km) of double-track mainline between Buffalo and Binghamton, New York. The idea had been studied as early as 1920, when William Z. Ripley, a professor of political economics at Harvard University, reported that a merger would have benefited both railroads. Forty years later, however, the Lackawanna was a shadow of its former financial self. Seeing no advantage in an end-to-end merger, Nickel Plate officials also rebuffed attempts by the DL&W, which owned a substantial block of Nickel Plate stock, to place one of its directors on the Nickel Plate board. (The Nickel Plate would later merge with the Norfolk and Western Railroad.)

Shoemaker next turned, in 1956, to aggressive, but unsuccessful, efforts to obtain joint operating agreements and even potential mergers with the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the Delaware and Hudson Railway.

Finally, Shoemaker sought and won a merger agreement with the Erie Railroad, the DL&W's longtime rival (and closest geographical competitor), forming the Erie Lackawanna Railroad.

The merger was formally consummated on October 17, 1960. Shoemaker drew much criticism for it, and would even second-guess himself after he had retired from railroading. He later claimed to have had a "gentlemen's agreement" with the E-L board of directors to take over as president of the new railroad. After he was pushed aside in favor of Erie managers, however, he left in disillusionment and became the president of the Central Railroad of New Jersey in 1962.

Even before the formal merger, growing ties between the Erie and Lackawanna led to the abandonment of the Lackawanna's mainline trackage between Binghamton and Buffalo. In 1958, the main line of the DL&W from Binghamton west to near Corning, which closely paralleled the Erie's main line, was abandoned in favor of joint operations, while the Lackawanna Cut-Off in New Jersey was single-tracked in anticipation of the upcoming merger. On the other hand, the Erie's Buffalo, New York and Erie Railroad was dropped from Corning to Livonia in favor of the DL&W's main line. Most passenger service was routed onto the DL&W east of Binghamton, with the DL&W's Hoboken Terminal serving all E-L passenger trains. In addition, a short segment of the Boonton Branch by Garret Mountain in Paterson, New Jersey, was sold off to the state of New Jersey to build Interstate 80. Ultimately, the west end of the Boonton Branch was combined with the Erie's Greenwood Lake Branch, while the eastern end was combined with the Erie's main line, which was abandoned through Passaic, New Jersey. Sacrificed was the Boonton Branch, a high-speed freight line thought to be redundant with the Erie's mainline. This would haunt E-L management less than a decade later (and Conrail management a decade after that).

Soon after the merger, the new E-L management shifted most freight trains to the "Erie side", the former Erie Railroad lines, leaving only a couple of daily freight trains traveling over the Lackawanna side. Passenger train traffic would not be affected, at least not immediately. This traffic pattern would remain in effect for more than ten years—past the discontinuation of passenger service on January 6, 1970—and was completely dependent on the lucrative interchange with the New Haven Railroad at Maybrook, New York. The Jan. 1, 1969 merger of the New Haven Railroad into the Penn Central Railroad changed all this: the New England Gateway was downgraded and later closed, causing dramatic traffic changes for the Lackawanna side. Indeed, as very little on-line freight originated on the Erie side (a route that was more than 20 miles longer than the DL&W route to Binghamton), once the Gateway was closed (eliminating the original justification for shifting traffic to the Erie side), virtually all the E-L's freight trains were shifted back to the Lackawanna side. After the New England Gateway closed, E-L's management was forced to downgrade the Erie side, and even considered its abandonment west of Port Jervis. In the meantime, the E-L was forced to run its long freights over the reconfigured Boonton Line, which east of Mountain View in Wayne, NJ meant running over the Erie's Greenwood Lake Branch, a line that was never intended to carry the level of freight traffic to which the E-L would subject it.

In 1972, the Central Railroad of New Jersey abandoned all its operations in Pennsylvania (which by that time were freight-only), causing additional through freights to be run daily between Elizabeth, NJ on the CNJ and Scranton on the E-L. The trains, designated as the eastbound SE-98 and the westbound ES-99, travelled via the Lackawanna Cut-Off and were routed via the CNJ's High Bridge Branch. This arrangement ended with the creation of Conrail.

During its time, the E-L diversified its shipments from the growing Lehigh Valley and also procured a lucrative contract with Chrysler to ship auto components from Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania. The E-L also aggressively sought other contracts with suppliers in the area, pioneering what came to be known as intermodal shipping. None of this could compensate for the decline in coal shipments, however, and as labor costs and taxes rose, the railroad's financial position became increasingly precarious although it was stronger than some railroads in the eastern U.S.

The opening of Interstates I-80, I-380, and I-81 during the early 1970s, which in effect paralleled much of the former Lackawanna mainline east of Binghamton, New York, caused more traffic to be diverted to trucks. This only helped to accelerate the E-L's decline. By 1976, it was apparent that the E-L was at the end of its tether, and it petitioned to join Conrail, a new regional railroad that was created on April 1, 1976, out of the remnants of seven bankrupt freight railroads in the northeastern U.S.

The E-L's rail property was legally conveyed into Conrail on April 1, 1976. Initially, Conrail's freight schedule did not change much from the E-L's due to labor contracts that restricted any immediate alterations. This, too, would change. In early 1979, Conrail suspended through freight service on the Lackawanna side, citing the E-L's early-1960s severing of the Boonton Branch near Paterson, New Jersey, and the grades over the Pocono Mountains as the primary reason for removing freight traffic from the entire Hoboken-Binghamton mainline and consolidating this service within its other operating routes.

The busy Morristown Line is the only piece of multi-track railroad on the entire 900-mile Lackawanna system that has not been reduced to fewer tracks over the years. In the 1986 photograph to the right, a set of Arrow III single units and an Arrow II married pair runs eastbound after passing the NJ Transit station in South Orange, New Jersey. The line was triple-tracked nearly a century prior, and remains so today.

The Lackawanna Cut-Off was abandoned in 1979 and its rails were removed in 1984. The line between Slateford Junction and Scranton remained in legal limbo for nearly a decade, but was eventually purchased, with a single track left in place. The Lackawanna Cut-Off's right-of-way, on the other hand, was purchased by the state of New Jersey in 2001 from funds approved within a $40 million bond issue in 1989. (A court later set the final price at $21 million, paid to owner Gerald Turco of Kearny, New Jersey.) NJ Transit has estimated it would cost $551 million to restore service to Scranton over the Cut-Off, a price which includes the cost of new trainsets. A 7.3-mile section of the Cut-Off between Port Morris and Andover, New Jersey, which was under construction has been delayed due to environmental issues on the Andover station site; the Cut-Off between Port Morris to Andover is slated to re-open for rail passenger service no earlier than 2021.

In 1979, Conrail sold most of the DL&W in Pennsylvania, with the DL&W main line portion between Scranton and Binghamton which includes the Nicholson Cutoff was bought by the Delaware and Hudson Railway. The D&H was purchased by the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1991. CPR continued to run this portion of the DL&W main line until 2015, when it was purchased by Norfolk Southern.

The Syracuse and Utica branches north of Binghamton have been retained, sold by Conrail to the DO Corp., which operates them as the northern division of the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway.

In 1997, Conrail was bought by CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway. On June 1, 1999, Norfolk Southern took over many of the Conrail lines in New Jersey, including most of the former DL&W. It also purchased the remnants of the former Bangor & Portland branch in Pennsylvania. Norfolk Southern continues to operate local freights on the lines. In 2015, it purchased the former DL&W main from Taylor, PA to Binghamton, NY from the Canadian Pacific Railway, which it continues to operate to this day.

NJ Transit took over passenger operations in 1983. The state of New Jersey had previously subsidized the routes operated by the E-L, and later Conrail. NJ Transit operates over former DL&W trackage on much of the former Morris & Essex Railroad to Gladstone and Hackettstown. In 2002, the transit agency consolidated the Montclair Branch and Boonton Line to create the Montclair-Boonton Line. NJ Transit also operates on the original eastern portion of the Boonton Line known as the Main Line. NJ Transit's hub is at Hoboken Terminal.

Trains on the Morristown Line run directly into New York's Pennsylvania Station via the Kearny Connection opened in 1996. This facilitates part of NJ Transit's popular Midtown Direct service. Formerly the line ran to a terminal in Hoboken and a transfer was required to pass under the Hudson river into Manhattan. This is the only section of former Lackawanna trackage that has more through tracks now than ever before.

Since the 1999 breakup of Conrail, the former DL&W main line from Scranton east to Slateford into Monroe County is owned by the Pennsylvania Northeast Regional Rail Authority. The Delaware-Lackawanna Railroad and Steamtown National Historic Site operates freight trains and tourist trains on this stretch of track, dubbed the Pocono Mainline (or Pocono Main). Under a haulage agreement with the Canadian Pacific Railway, the D-L runs unit Canadian grain trains between Scranton and the Harvest States Grain Mill at Pocono Summit, Pennsylvania. Excursion trains, hauled by Nickel Plate 765 and other locomotives, run from Steamtown to Moscow and Tobyhanna on the Pocono Mainline.

The D-L also runs Lackawanna County's tourist trolleys from the Electric City Trolley Museum, under overhead electrified wiring installed on original sections of the Lackawanna and Wyoming Valley Railroad purchased by Lackawanna County. It also runs trains on a remnant of the DL&W Diamond branch in Scranton.

In 2006, the Monroe County and Lackawanna County Railroad Authorities formed the Pennsylvania Northeast Regional Rail Authority to accelerate the resumption of commuter train service between New York City and Scranton.

Some of the main line west of Binghamton in New York state is also abandoned, in favor of the Erie's Buffalo line via Hornell between Waverly, and Corning. The longest remaining main line sector is Painted Post-Wayland, with shortline service provided by B&H Railroad (Bath & Hammondsport, a division of the Livonia, Avon, and Lakeville Railroad). Shorter main line remnants are Groveland-Greigsville (Genesee & Wyoming) and Lancaster-Depew (Depew, Lancaster & Western). The Richfield Springs branch was scrapped in 1998 after being out of service for years; as of 2012, the new owners of the right-of-way are looking for a new narrow-gauge shortline passenger operator. The Cincinnatus Branch, abandoned by Erie Lackawanna in 1960, was partially rebuilt for an industrial spur about 1999. Tracks from Binghamton to Buffalo remain mostly intact, save one short section between Wayland and Dansville and a 40-mile section outside of Buffalo, meaning it’s possible to travel nearly all the route of the late-1950s Phoebe Snow from Scranton to Buffalo.

As of 2018, the Reading Blue Mountain and Northern operates the former Keyser Valley branch from Scranton to Taylor, as well as the former Bloomsburg branch from Taylor to Coxton Yard in Duryea. The Luzerne and Susquehanna Railway operates the former Bloomsburg branch from Duryea to Kingston. The North Shore Railroad (Pennsylvania) operates the former Bloomsburg branch from Northumberland to Hicks Ferry.

In 2012, the Lackawanna Railroad paint scheme returned to the rails on Norfolk Southern NS #1074, an EMD SD70ACe locomotive, as part of Norfolk Southern's celebration of 20 of its predecessor lines.A bond is a document of title for a loan. Bonds are issued, not only by businesses, but also by national, state or city governments, or other public bodies, or sometimes by individuals. Bonds are a loan to the company or other body. They are normally repayable within a stated period of time. Bonds earn interest at a fixed rate, which must usually be paid by the undertaking regardless of its financial results. A bondholder is a creditor of the undertaking.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries