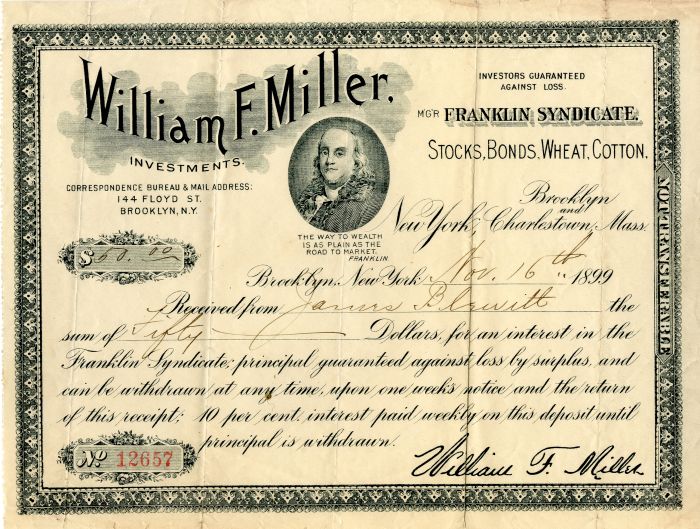

William F. Miller Investments Interest Receipt - 1899 dated Stock Certificate

Inv# FA1020 Stock

Ponzi Scheme Item - Franklin Syndicate Interest Receipt depicting Benjamin Franklin by William F. Miller Investments - Newly Discovered dated 1899. Measures 8.5" wide by 6.5" tall.

Long before con man Bernie Madoff there was the Franklin Syndicate, which only goes to prove once again the old saws about a fool and his money and/or if it sounds too good to be true… The Franklin Syndicate was a Ponzi Scheme that collapsed in Brooklyn in November 1899, sucking the life savings from thousands of people across the country. The front man of the Syndicate went to prison for 6 years and walked away with nothing except a debilitating case of consumption, while two of his partners managed to skate away with a bunch of money. One of them served a few of years for fraud in return for enough money to live a life of leisure, but the other managed to escape punishment altogether and lived happily ever after over in Europe. A Ponzi scheme is a pretty simple con. Named for Charles Ponzi, an Italian immigrant to the United States who managed a con that put even the Franklin Syndicate to shame, the game is simply to promise a high rate of return on an investment and use the proceeds of the initial investment to pay the interest or dividend. Ponzi didn’t invent the scheme, but it bears his name anyway.

Essentially it works like this: I promise you a return of 10 percent per week on your $100 investment (520 percent per year). The first week I give you $10 of your $100 back and tell you it’s the interest you earned. You then either take the $10 and leave the initial investment alone or reinvest the $10. If you reinvest, you think you have $110 earning 520 percent, but actually there is only at most the original $100 left. Chances are there is less than that because I’m a con man and I’m using your money for my own nefarious purposes. You think this is such a good deal that you bring in your friends and soon lots of people are investing with me. Because the return is so good, most people let the investment ride and reinvest their supposed earnings — like most of us do with bank accounts or 401(k)s. Meanwhile, I’m living the high life on your money. As long as no one wants their initial investment back, everything’s cool. Eventually, though, people do want their money back, or there just isn’t enough left to continue to pay the returns and the whole house of cards collapses.

The Franklin Syndicate The Franklin Syndicate began quietly in Brooklyn in March 1899 when the president of a prominent Brooklyn church’s Christian Endeavor Society, William F. Miller, 25, convinced three of his Sunday school friends to give him some money to invest in the stock market. Miller, who had previously unsuccessfully speculated in a small way on Wall Street, promised them a 10 percent per week return on their investments because he was a party to “inside information.” Oscar Bergstrom, 20, became the first investor in Miller’s Bucket Shop when he gave Miller $10 on March 16, 1899 and received a receipt that read, in part: “The principal guarantied (sic) against loss. Dividends weekly from $1 upwards till principal is withdrawn.” On April 8, Bergstrom invested another $10 and received an identical receipt. Miller quickly expanded the scheme by drawing in the other two men and inducing them to bring in others by promising a 5 percent commission on a deposit from any person they brought in to the syndicate. As the con became more successful, Miller branched out from Brooklyn and began advertising in newspapers around the country.

As an indication of how successful the Franklin Syndicate had become, in the summer of 1899 Miller spent $32,000 on advertising in 800 newspapers. He also sent out official-looking circulars and letters. In this day and age Miller’s claims would have brought down a federal indictment before the ink dried on the paper, but back then the laissez-faire attitude of the government meant that it was caveat emptor for the investor. “My intention is to make the Franklin Syndicate one of the largest and strongest syndicates operating in Wall Street, which will enable us to manipulate stocks, putting them up or down as we desire,” he wrote. “We also guarantee you against loss, there being absolutely no risk of losing, as we depend entirely on inside information.” Miller also managed to take advantage of the burgeoning public relations business, hiring a man named Cecil Leslie to place positive articles in the papers. One article, submitted as evidence at Miller’s fraud trial, carried the headline: “Wall Street Astonished. William F. Miller’s Franklin Syndicate a Big Winner. 10 Per Cent. a Week Profit. All Former Efforts in Financial Operations Eclipsed by a New Wizard in the Realms of Stock Manipulation.” In fact Miller only speculated on stocks once with funds received from his investors. He took $1,000 and managed to turn it into $5.60 in short order. From that point on he never bothered to invest again. Throughout the summer the Syndicate flourished.

Miller and his 22 employees were literally knee-deep in money in his store in Brooklyn. And we mean literally: Cash was stuffed in boxes and drawers around the building, there not being enough room in the small safe Miller purchased. “Crowds of depositors appeared at the house,” wrote one account. “Some to deposit money, and others to receive their dividends. They extended in long lines from the office to the street, awaiting their turns, each in sight of the other; those depositing receiving encouragement to deposit by seeing the dividend drawers taking their profits.” At the height of Miller’s con, there were an estimated 12,000 subscribers. His records showed that in October and November 1899 he was receiving anywhere between $20,000 and $63,000 per day. A dollar in 1900 had approximately the same buying power as $22 today, so it is obvious that Miller had more money than Croesus. The Franklin Syndicate was not just Miller’s brainchild. Early on in the enterprise he enlisted the help of Edward Schlessinger, who rather smartly realized that nothing good lasts forever and demanded his cut — one-third of the take — in cash each day. That was good for Schlessinger and ultimately bad for Miller because it required that the men actually keep a record of what they took in.

Schlessinger hid his money away somewhere while Miller, for some strange reason, seemed to think that the scheme could last forever. He never bothered to squirrel away anything. Another problem for Miller was the fact that everyone who deposited money with the Syndicate got a receipt — essentially a signed confession bearing Miller’s name. The third partner in the Syndicate, brought in in October 1899, managed to come up with a scheme to get the dupes to return the receipts so the Syndicate could destroy them. Col. Robert Ammon was a New York attorney with a shady past who always seemed to be representing the semi-crooked robber baron types who frequented Wall Street at the time. When the more legitimate newspapers of the city began looking closer at the actions of the Franklin Syndicate, Ammon connected with Miller and offered to run interference. He realized that all of those receipts floating around were ammunition for the law, and he advised Miller to get them back by incorporating the Franklin Syndicate. Miller sent out a letter to all depositors, alerting them to a forthcoming incorporation.

In return for each dollar invested, the depositor would be issued a share of the corporation. “As all depositors are entitled to stock certificates in the corporation, it will be necessary to compare the receipt you now hold with my books, and just as soon as I receive your receipts I will immediately send you your stock certificates,” he wrote. Miller didn’t stop there. He promised his investors that their shares would quickly multiply in value. Not only would they continue to receive their 520 percent annual return, they would also enjoy capital gains from the increase in the price of Franklin Syndicate stock. “It is my belief that Franklin Syndicate shares will be selling at $400 to $500 a share before March 1st next,” he wrote. Miller was even more audacious later in his letter: “After December 2nd…I shall open no new accounts for less than $50,” he wrote. “All accounts which I now have of less than $50 will have to deposit sufficient to make their account $50, or they will not be taken into the new corporation.”

Little did Miller know, but Ammon was planning his own con with Miller as the dupe. While the newspapers continued to accept Miller’s advertisements, their reporters wrote scathing pieces about the obvious con Miller was running. Meanwhile, government officials tried in vain to find someone willing to make a complaint against the syndicate. “Post Office Inspector William S. McGuinness has had Miller’s syndicate under observation for several weeks,” wrote the New York Times. “He could find nothing in Brooklyn on which to proceed against the concern, so he wrote 250 letters to Miller’s customers in various parts of the United States asking them if they had any complaint to make. All his replies expressed satisfaction with Miller.” Local police had the same problem. “I have yet to hear any of that man’s customers speak against him,” said Capt. James Reynolds of the Brooklyn police department. “I tell you that even yet I do not know what to make of Miller. The people in the neighborhood all had faith in him and many of the merchants there honor his checks even now.” The investors blamed the media. “Mr. Miller has never failed us,” one woman told the Times. “I put in $100 six weeks ago and have taken $60 out. It’s these newspapers and bankers that are causing the trouble. Nobody believes the papers. It’s envy. They’d like to make money themselves.” But by November 24, 1899, the game was up, Miller and Schlessinger were wanted men and Ammon put his secret plan into motion.

The men huddled at Ammon’s office to formulate an escape plan. Ammon advised Miller to flee to Montreal, Canada, to avoid arrest. Schlessinger said he was headed for Europe. He gathered his cash in a large satchel and was never seen again. The best estimate is that Schlessinger got away with $145,000. It takes a thief to catch a thief and the slimy lawyer was about to show Miller that even con artists get conned. Ammon convinced Miller that it would be safest to hide the money he managed to grab in Ammon’s own accounts. As attorney for Miller, Ammon was protected by privilege, so even if Miller was punished for the con, the creditors would never see their money again. It is an untruth cut from whole cloth. Miller thought that was a good idea and with Ammon carrying a suitcase with $35,000 in cash, they deposited the swag in the Wells, Fargo & Co. bank. In addition, Miller transferred a certificate of deposit for $100,000 and a check for $10,000, which represented his whole take from the scam. But Ammon was not finished. As long as the sucker had a dime, the lawyer wanted it. Shortly after, the gullible Miller turned over $40,000 in government bonds and Miller’s father gave Ammon $65,000 in New York Central Railroad bonds.

The next day Miller received word that he had been indicted in Kings County for fraud and warrants were already signed. After ducking through a drug store and a Chinese laundry to lose a trailing detective, Miller showed up at Ammon’s office where the lawyer made arrangements to get him over the border. Miller left his wife and young daughter in Brooklyn and hid out in Montreal for a couple of weeks until he was traced by New York police and brought back to Kings County for trial. His trial was a cut-and-dried event and he was given a 10-year prison term. Ammon had Miller by the short hairs and let him know it. In return for Miller’s silence about Ammon’s involvement in the scam, Miller’s wife and daughter would receive a $5 week payment while he languished in jail. “The character of the gentleman is well illustrated by the fact,” wrote Arthur Train, the assistant DA who prosecuted the case, “that later when paying Mrs. Miller her miserable pittance of five dollars per week, he explained to her that ‘he was giving her that out of his own money, and that her husband owed him.'”

For three years the Kings County District Attorney struggled to build a case against Ammon, but without Miller’s cooperation, there was nothing to connect the lawyer to the con. Eventually Miller, seriously ill with consumption, agreed to testify against Ammon. The support for his family stopped immediately when Ammon was charged and brought to trial. In 1903 Robert Ammon was convicted of theft of $30,500 and sentenced to four years in prison. Presumably he served his time and went on to enjoy the rest of his ill-gotten gains in comfort. Miller’s fate is less certain. He was released after serving about 6 years of his sentence, and most reports say that he was terminally ill with tuberculosis. Another report, however, claims that he went on to run a grocery. The former is more likely, as he was quite sick at Ammon’s trial, and early in the 20th century TB victims did not recover to become grocers. (By Mark Gribben)

A stock certificate is issued by businesses, usually companies. A stock is part of the permanent finance of a business. Normally, they are never repaid, and the investor can recover his/her money only by selling to another investor. Most stocks, or also called shares, earn dividends, at the business's discretion, depending on how well it has traded. A stockholder or shareholder is a part-owner of the business that issued the stock certificates.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries