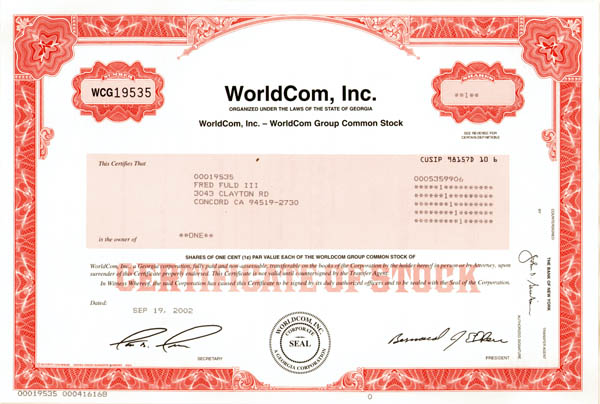

Worldcom Incorporated - Stock Certificate - Famous Scandal

Inv# GS1361 Stock

Security-Columbian US Banknote Co. So infamous and so important in our recent financial history!!! Enron and Worldcom have been very popular stocks due to extensive media coverage.

MCI, Inc. (previously Worldcom and MCI WorldCom) was a telecommunications company. For a time, it was the second largest long-distance telephone company in the United States, after AT&T. Worldcom grew largely by acquiring other telecommunications companies, including MCI Communications in 1998, and filed bankruptcy in 2002 after an accounting scandal, in which several executives, including CEO Bernard Ebbers, were convicted of a scheme to inflate the company's assets. In January 2006, the company, by now renamed MCI, was acquired by Verizon Communications and was later integrated into Verizon Business.

Worldcom was originally headquartered in Clinton, Mississippi before relocating to Ashburn, Virginia when it changed its name to MCI.

In 1983, in a coffee shop in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Bernard Ebbers and 3 other investors formed Long Distance Discount Services, Inc. based in Jackson, Mississippi and in 1985, Ebbers was named chief executive officer. The company acquired over 60 telecommunications firms and in 1995, it changed its name to WorldCom.

The company became a public company as a corporation in 1989 as a result of a merger with Advantage Companies Inc. The company name was changed to LDDS WorldCom in 1995, and relocated to Clinton, Mississippi.

The company grew rapidly in the 1990s, after completing several mergers and acquisitions.

Worldcom's first major acquisition was in 1992 with the $720 million acquisition of Advanced Telecommunications Corporation, outbidding larger rivals Sprint Corporation and AT&T to secure the deal, making Worldcom a larger player in the telecoms market.

Other acquisitions included: Metromedia Communication Corp. and Resurgens Communications Group in 1993, IDB Communications Group, Inc (1994), Williams Technology Group, Inc. (1995), and MFS Communications Company (1996), and MCI in 1998. The acquisition of MFS included UUNET Technologies, Inc., which had been acquired by MFS shortly before the merger with WorldCom. In February 1998, WorldCom acquired CompuServe from its parent company H&R Block. WorldCom then retained the CompuServe Network Services Division, sold its online service to America Online, and received AOL's network division, ANS. WorldCom acquired the corporate parent of Digex, Intermedia Communications in June 2001 and then sold all of Intermedia's non-Digex assets to Allegiance Telecom.

On November 4, 1997, WorldCom and MCI Communications announced a $37 billion merger to form MCI WorldCom, making it the largest corporate merger in U.S. history. On September 15, 1998, the merger was consummated, forming MCI WorldCom. MCI divested itself of its "internetMCI" business to gain approval from the U.S. United States Department of Justice.

On October 5, 1999, Sprint Corporation and MCI WorldCom announced a $129 billion merger. Had the deal been completed, it would have been the largest corporate merger in history. The merged company would have surpassed AT&T as the largest communications company in the United States. However, the deal floundered due to opposition from the United States Department of Justice and the European Union on concerns that it would create a monopoly. On July 13, 2000, the boards of directors of both companies terminated the merger. Later that year, MCI WorldCom renamed itself "WorldCom".

Between September 2000 and April 2002, the board of directors of Worldcom authorized several loans and loan guarantees to CEO Bernard Ebbers so that he would not have to sell his Worldcom shares to meet margin calls as the share price plummeted during the bursting of the dot-com bubble. By April 2002, the board had lost patience with these loans. Directors also believed that Ebbers didn't seem to have a coherent strategy after the Sprint merger collapsed. On April 26, the board voted to ask for Ebbers' resignation. Ebbers formally resigned on April 30, 2002 and was replaced by John W. Sidgmore, former CEO of UUNET. As part of his departure, Ebbers's loans were consolidated into a single $408.2 million promissory note. In 2003, Ebbers defaulted on the note and Worldcom foreclosed on many of his assets.

Beginning modestly during mid-1999 and continuing at an accelerated pace through May 2002, Ebbers, CFO Scott Sullivan, controller David Myers and general accounting director Buford "Buddy" Yates used fraudulent accounting methods to disguise WorldCom's decreasing earnings in order to maintain the company's stock price.

The fraud was accomplished primarily in two ways:

- Booking "line costs" (interconnection expenses with other telecommunication companies) as capital expenditures on the balance sheet instead of expenses.

- Inflating revenues with bogus accounting entries from "corporate unallocated revenue accounts".

In June 2002, a small team of internal auditors at WorldCom led by division vice president Cynthia Cooper and senior associate Eugene Morse worked together, often at night and secretly, to investigate and reveal what was ultimately discovered to be $3.8 billion worth of fraudulent entries in WorldCom's books. The investigation was triggered by suspicious balance sheet entries discovered during a routine capital expenditure audit. Cooper notified the company's audit committee and board of directors in June 2002. The board moved swiftly, forcing Myers to resign and firing Sullivan when he refused to resign. Arthur Andersen withdrew its audit opinion for 2001. Cooper and her team had exposed the largest accounting fraud in American history, displacing the fraud uncovered at Enron less than a year earlier. It would remain the largest accounting fraud ever uncovered until the exposure of Bernard Madoff's giant Ponzi scheme in 2008.

By this time, the U. S. Attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission were already looking into the matter as well. The SEC launched a formal inquiry into these matters on June 26, 2002. The SEC was already investigating WorldCom for questionable accounting practices. By the end of 2003, it was estimated that the company's total assets had been inflated by about $11 billion.

The fraud came to light just days after Andersen was convicted of obstruction of justice in the Enron scandal, a verdict that effectively put Andersen out of business. In his post-mortem of the Enron scandal, Conspiracy of Fools, journalist Kurt Eichenwald argued that Andersen's failure to uncover WorldCom's deceit would have brought Andersen down even if it had escaped the Enron fraud unscathed.

On July 21, 2002, WorldCom filed bankruptcy in the largest such filing in United States history at the time (overtaken by the bankruptcies of both Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual in a span of eleven days during September 2008). The WorldCom bankruptcy proceedings were held before U.S. Federal Bankruptcy Judge Arthur Gonzalez, who simultaneously heard the Enron bankruptcy proceedings, which were the second largest bankruptcy case resulting from one of the largest corporate fraud scandals. None of the criminal proceedings against WorldCom and its officers and agents were originated by referral from Gonzalez or the Department of Justice lawyers. By the bankruptcy reorganization agreement, the company paid $750 million to the SEC in cash and stock in the new MCI, which was intended to be paid to wronged investors.

Effective December 16, 2002, Michael Capellas became chairman and chief executive officer. On April 14, 2003, WorldCom changed its name to MCI, and relocated its corporate headquarters from Clinton, Mississippi, to Ashburn, Virginia.

Even before then, however, employees from the MCI side of the merger had taken over top executive posts, while many longtime executives from the old WorldCom were pushed out. In late 2002, the company began moving most of its operations to its campus in Ashburn, which had opened in 2000. Capellas, for instance, spent most of his time in Northern Virginia. After the name change, one executive from the old MCI said, "We're taking our company back." Another wrote in an email, "My company was not founded in a motel coffee shop."

In May 2003, in a controversial deal, the company was given a $45 million no-bid contract by the United States Department of Defense to build a cellular phone service in Iraq as part of the U.S.-led reconstruction effort despite the fact that the company was not known for its expertise in building wireless networks.

WorldCom agreed to pay a civil penalty of $2.25 billion to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The deal was approved by federal judge Jed Rakoff in July 2003. In a sweeping consent decree, the SEC and Rakoff essentially took control of WorldCom. Rakoff appointed former SEC chairman Richard C. Breeden to oversee WorldCom's compliance with the SEC agreement. Breeden actively involved himself with the management of the company, and prepared a report for Rakoff, titled Restoring Trust, in which he proposed extensive corporate governance reforms, as part of an effort to "cast the new MCI into what he hoped would become a model of how shareholders should be protected and how companies should be run".

The company emerged from bankruptcy in 2004 with about $5.7 billion in debt and $6 billion in cash. About half of the cash was intended to pay various claims and settlements. Previous bondholders ended up being paid 35.7 cents on the dollar, in bonds and stock in the new MCI company. The previous stockholders' stock was cancelled.

It had yet to pay many of its creditors, who had waited for two years for a portion of the money owed. Many of the small creditors included former employees, primarily those who were dismissed during June 2002 and whose severance and benefits were withheld when WorldCom filed for bankruptcy.

Citigroup settled with Worldcom investors for $2.65 billion on May 10, 2004. In March 2007, 16 of WorldCom's 17 former underwriters reached settlements with investors.

On March 15, 2005, Bernard Ebbers was found guilty of all charges and convicted of fraud, conspiracy and filing false documents with regulators — all related to the $11 billion accounting scandal. Other former WorldCom officials charged with criminal penalties in relation to the company's financial misstatements include former CFO Scott Sullivan (entered a guilty plea on March 2, 2004, to one count each of securities fraud, conspiracy to commit securities fraud, and filing false statements), former controller David Myers (pleaded guilty to securities fraud, conspiracy to commit securities fraud, and filing false statements on September 27, 2002), former accounting director Buford Yates (pleaded guilty to conspiracy and fraud charges on October 7, 2002), and former accounting managers Betty Vinson and Troy Normand (both pleading guilty to conspiracy and securities fraud on October 10, 2002).

On July 13, 2005, Bernard Ebbers received a sentence that would have kept him imprisoned for 25 years. At time of sentencing, Ebbers was 63 years old. On September 26, 2006, Ebbers surrendered himself to the Federal Bureau of Prisons prison at Oakdale, Louisiana, the Oakdale Federal Correctional Institution, to begin serving his sentence; he was released in late 2019 for health reasons and died in February 2020, after serving 13 years of his sentence.

In December 2005, Microsoft announced a partnership with MCI to provide Windows Live Messenger customers voice over IP service to make telephone calls - called "MCI Web Calling". After the merger with Verizon, this product was renamed "Verizon Web Calling".

In January 2006, the company was acquired by Verizon Communications and was later integrated into Verizon Business.

The WorldCom scandal was a major accounting scandal that came to light in the summer of 2002 at WorldCom, the USA's second largest long-distance telephone company at the time. From 1999 to 2002, senior executives at WorldCom led by founder and CEO Bernard Ebbers orchestrated a scheme to inflate earnings in order to maintain WorldCom's stock price. The fraud was uncovered in June 2002 when the company's internal audit unit, led by vice president Cynthia Cooper, discovered over $3.8 billion of fraudulent balance sheet entries. Eventually, WorldCom was forced to admit that it had overstated its assets by over $11 billion. At the time, it was the largest accounting fraud in American history.

In December 2000, WorldCom financial analyst Kim Emigh was told to allocate labor for capital projects in WorldCom's network systems division as an expense rather than book it as a capital project. By Emigh's estimate, the order would have affected at least $35 million in capital spending. Believing that he was being asked to commit tax fraud, Emigh pressed his concerns up the chain of command, notifying an assistant to WorldCom chief operating officer Ron Beaumont. Within 24 hours, it was decided not to implement the directive. However, Emigh was reprimanded by his immediate superiors, and subsequently laid off in March 2001.

Emigh, who was from the MCI half of the 1997 WorldCom/MCI merger, later told Fort Worth Weekly in May 2002 that he had expressed concerns about MCI's spending habits for years. He believed that things had been reined in somewhat after WorldCom took over, but he was still unnerved by vendors billing WorldCom for exorbitant amounts. The Fort Worth Weekly article was eventually read by Glyn Smith, an internal audit manager at WorldCom headquarters in Clinton, Mississippi. After examining it, he suggested to his boss, Cooper, that she should start that year's scheduled capital expenditure audit a few months early. Cooper agreed, and the audit began in late May.

During a meeting with the auditors, corporate finance director Sanjeev Sethi explained that differing amounts in two capital spending expenditures related to "prepaid capacity." No one in the room had ever heard that term before. When pressed for an explanation, Sethi said that he did not know what the term meant, even though his division approved capital spending requests. He referred the auditors to corporate controller David Myers. Suspicious, Cooper asked Mark Abide, head of property accounting, about the term. Abide was not familiar with it either, even though he had made several entries about prepaid capacity in WorldCom's computerized accounting system.

Cooper and Smith asked senior associate Eugene Morse, one of the "techies" on the internal audit team, to peruse the accounting system for any references to prepaid capacity. Morse was eventually able to find one and trace it through the system. However, the amounts were bouncing between accounts in an unusual manner, resulting in a large round amount moving from WorldCom's income statement to its balance sheet. Cooper asked Morse to see if there was another prepaid capacity entry that moved around in similar fashion. Morse went to work, but pulled so much data that he frequently clogged up the accounting servers. Eventually, he and the rest of the team began working at night. Finally, on June 10, Morse found more entries about "prepaid capacity"; large amounts had been transferred from the income statement to the balance sheet from the third quarter of 2001 to the first quarter of 2002.

Soon afterward, chief financial officer Scott Sullivan, Cooper's immediate supervisor, called Cooper in for a meeting about audit projects, and asked the internal audit team to walk him through recently completed audits. When Smith's turn came, Cooper asked about the prepaid capacity entries. Sullivan claimed that it referred to costs related to SONET rings and lines that were either not being used at all or were seeing low usage. He claimed those costs were being capitalized because the costs associated with line leases were fixed even as revenue dropped. He planned to take a restructuring charge in the second quarter of 2002, after which WorldCom would allocate these costs between restructuring charges and expenses. He asked Cooper to postpone the capital-expenditure audit until the third quarter, heightening Cooper's suspicions.

That night, Cooper and Smith called Max Bobbitt, a WorldCom board member and the chairman of the Audit Committee, to discuss their concerns. Bobbitt was concerned enough to tell Cooper to discuss the matter with Farrell Malone of KPMG, WorldCom's external auditor. KPMG had inherited the WorldCom account when it bought Arthur Andersen's Jackson practice in the wake of Andersen's indictment for its role in the accounting scandal at Enron. By this time, the internal audit team had found 28 prepaid capacity entries dating back to the second quarter of 2001. By their calculations, if not for those entries, WorldCom's $130 million profit in the first quarter of 2002 would have become a $395 million loss. Despite this, Bobbitt thought it was premature to discuss the matter with the Audit Committee at that point. He did, however, discuss the matter with Sullivan, and assured Cooper that he would have support for those entries by the following Monday.

Cooper decided not to wait to discuss the matter with Sullivan. She decided to ask the accountants who made those entries to provide support for them herself. Beforehand, she asked Kenny Avery, who had been Andersen's lead partner on the WorldCom account before KPMG took over, if he knew about prepaid capacity. Avery had never heard of the term, and knew of nothing in Generally Accepted Accounting Principles that allowed for capitalizing line costs. Andersen, it turned out, had never tested WorldCom's capital expenditures for it.

Cooper and Smith then questioned Betty Vinson, the accounting director who made the entries. To their surprise, Vinson admitted she had made the entries without knowing what they were for or seeing support for them. She had done so at the direction of Myers and general accounting director Buford Yates. When Cooper and Smith spoke with Yates, he admitted that he did not know what prepaid capacity was. Yates also claimed that accountants reporting to him booked entries at Myers' direction.

Finally, the internal auditors spoke with Myers. He admitted that there was no support for the entries. In fact, they had been booked "based on what we thought the margins should be," and there were no accounting standards that supported them. He admitted that the entries should have never been made, but it was difficult to stop once they started. Although he was uncomfortable with the entries, he never thought that he would have to explain them to regulators. The following day, Farrell met with Sullivan and Myers, and concluded that their rationale for the entries made sense "from a business perspective, but not an accounting perspective." In response, Sullivan, Myers, Yates and Abide scrambled to find amounts that were expensed when they should have been capitalized in hopes of offsetting the prepaid capacity entries. They believed that the only other alternative was an earnings restatement.

Bobbitt finally called an Audit Committee meeting for June 20. By this time, Cooper's team had discovered over $3 billion in questionable transfers from line cost expense accounts to assets from 2001 to 2002. At the meeting, Farrell stated that there was nothing in GAAP that would allow those entries. Sullivan claimed that WorldCom had invested in expanding the telecom network from 1999 onward, but the anticipated expansion in customer usage never occurred. He argued that the entries were justified on the basis of the matching principle, which allowed costs to be booked as expenses so they align with any future benefit accrued from an asset. He also contended that since capital assets were worth less than what the books said they should be, he reiterated his proposal for a restructuring charge, or an "impairment charge," as he called it, for the second quarter of 2002. He claimed that Myers could provide support for the entries. The committee gave him until the following Monday to get support.

Over the weekend, Cooper and her team discovered several more suspicious "prepaid capacity" entries. All told, the internal audit unit had discovered a total of 49 prepaid capacity entries detailing $3.8 billion in transfers spread out across all of 2001 and the first quarter of 2002. Several of them were keyed in on explicit directions from Sullivan and Myers under the line "SS entry." While some of the suspicious entries were made by directors and managers, others were made by lower-level accountants who didn't understand the seriousness of what they were doing. While meeting with another accounting director, Troy Normand, they learned about more potentially illicit accounting. According to Normand, management had drawn down the company's cost reserves in portions of 2000 and 2001 to artificially reduce expenses.

At the same time, the Audit Committee asked KPMG to conduct its own review. KPMG discovered that Sullivan had moved system costs across a number of property accounts, allowing them to be booked as capital expenditures. The expenses were spread out so they weren't initially obvious. When KPMG asked Andersen's former WorldCom engagement team about the entries, the Andersen accountants said they would have never approved of the entries had they known about them. Sullivan was asked to present a written explanation for his actions by Monday.

At an Audit Committee meeting that Monday, Sullivan presented a white paper explaining his reasoning. The Audit Committee and KPMG were not persuaded. They concluded that the amounts were transferred with the sole purpose of meeting Wall Street targets, and the only acceptable remedy was to restate corporate earnings for all of 2001 and the first quarter of 2002. Andersen withdrew its audit opinion for 2001, and the board demanded Sullivan and Myers' resignations.

On June 25, after the amount of the illicit entries was confirmed, the board accepted Myers' resignation and fired Sullivan when he refused to resign. On the same day, WorldCom executives briefed the SEC, revealing that it would have to restate its earnings for the next five quarters. Later that day, WorldCom publicly admitted that it had overstated its cash flow by over $3.8 billion over the previous five quarters. The disclosure came at a particularly bad time for WorldCom. Even before the scandal broke, its credit had been reduced to junk status, and its stock had lost over 94 percent of its value. It had been facing a separate SEC investigation into its accounting that had started earlier in the year, and was laboring under $30 billion in debt. Amid rumors of bankruptcy, WorldCom said it would lay off 17,000 employees.

The federal government had already begun an informal inquiry earlier in June, when Vinson, Yates, and Normand secretly met with SEC and Justice Department officials. The SEC filed civil fraud charges against WorldCom on June 26, speculating that WorldCom had engaged in a concerted effort to manipulate its earnings in order to meet Wall Street targets and support its stock price. Additionally, it claimed that the scheme had been "directed and approved by senior management"–thus hinting that executives higher up on the org chart than Sullivan and Myers had known about the scheme.

In 2005 Ebbers was found guilty by a jury for fraud, conspiracy, and filing false documents with regulators. He was subsequently sentenced to 25 years in prison. However he was released in December 2019 due to declining health. Ebbers would die in February 2020.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act is said to have passed due to scandals such as WorldCom and Enron.

WorldCom would later merge with Verizon in January 2005.

A stock certificate is issued by businesses, usually companies. A stock is part of the permanent finance of a business. Normally, they are never repaid, and the investor can recover his/her money only by selling to another investor. Most stocks, or also called shares, earn dividends, at the business's discretion, depending on how well it has traded. A stockholder or shareholder is a part-owner of the business that issued the stock certificates.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries